-

등록된 팝업이 없습니다.

지난전시

지난전시

- 전시

- 지난전시

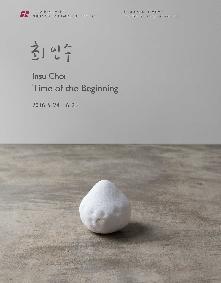

최인수 초대전

- 전시명:Time of the Beginning

- 전시장소:대구보건대학교 인당박물관

- 전시기간:2016-05-24 ~ 2016-06-25

최인수 초대전 <Time of the Beginning>

‘처음의 시간’

어느 누구에게나 어떤 일이건 처음의 시간은 있죠.

언제나 시작의 순간은 설렘과 두려움, 떨림과 기다림으로 더없이 소중하지만 그 순간을 항상 기억하기란 쉽지 않습니다.

봄 향기 가득한 5월 인당뮤지엄에서는 최인수 작품의 순간을 함께 기억하고자 합니다.

여러분들도 마음속에 간직해있던 내 인생 처음의 순간을 이번 전시를 통해 함께 꺼내보시기 바랍니다.

There is first time for everything for everyone.

These words, 'first time', seem to always bring mystiques of trembling, yearning and even fear to make this special experience even more special; however, it is also not quite easy to remember that very moment for a long period of time.

In this May filled with the scent of the spring season, I intend to remember the works created by Chio In-su at Indang Museum and share this moment for many years to come.

I sincerely hope all of you to take this opportunity to bring out and revisit your special moments of the first time through this exhibition.

Nam, Sung hee

최 인 수

서울대학교 미술대학 명예교수

독일 국립 칼스루헤 미술대학 수학

서울대학교 미술대학 대학원 졸업

개인전

2016 인당뮤지엄, 대구

갤러리 아트링크, 서울

2013 갤러리 시몬, 서울

갤러리 데이트, 부산

2010 갤러리 아트링크, 서울

2009 BIBI Space, 대전

2004 금산갤러리, 서울

1995 갤러리 서미, 서울

1933 토탈미술관, 서울

1991 갤러리 서미, 서울

1985 한국 미술관, 서울

1982 공간 화랑, 서울

단체전

2015 사물의 소리를 듣다, 국립현대미술관, 과천

2014 사유로서의 형식-드로잉의 재발견, 뮤지엄 산, 원주

2013 White and White-Dialog Between Korea and Italy,

Museo Carlo Bilotti, Rome, 이탈리아

한국미술의 발자취, 서울대학교 미술관, 서울

국립현대미술관 서울관 개관전, 서울

2012 세라믹스 코뮌, 아트선재, 서울

Steel Life, 포항시립미술관, 포항

드로잉의 두 호흡-직관하거나 포용하기, 갤러리 두인, 서울

2011 기氣가 차다, 대구미술관 개관전, 대구

조각가의 드로잉, 소마미술관, 서울

2010 서울미술대전‘한국현대조각2010’, 서울시립미술관, 서울

2009 연천국제조각 심포지움, 연천

2008 Scultura Internazionale ad Aglie, Scultura Natura, Torino, 이탈리아

2007 공간을 치다, 경기도 미술관, 안산

한국 현대조각의 정신, 어제와 오늘, 마나스아트센터, 양평

2006 Simply Beautiful, Centre PasquArt, Biel, 스위스

Fluid Artcanal 06/01 International, Le Landeron, 스위스

현대미술의 초대, 서울대학교 미술관, 서울

고요의 숲, 서울시립미술관, 서울

2005 서울조각회, 인사갤러리, 서울

2004 문자향(文字香), 김종영미술관, 서울

정지와 움직임, 서울올림픽미술관 개관전, 서울

되돌아보는 한국현대조각의 위상, 모란미술관, 남양주

2002 서울미술대전, 서울시립미술관, 서울

빔;inter-images, 토탈미술관, 서울

2001 용산조각공원 국제조각 심포지움

2000 뒤죽박죽, 토탈미술관, 서울

국제조각전 ‘원을 넘어서 Beyond the Circle', 모란미술관, 남양주

1999 공간의 본질 관조의 거리, 부산시립미술관, 부산

한국현대조각의 표상 - ‘99, 갤러리우덕, 서울

1998 물질과 작가의 흔적, 모란갤러리, 서울

올림픽조각공원 심포지움, 서울올림픽 조각공원, 서울

1997 자연과 사유, 박여숙 화랑, 서울

0의 소리, 성곡미술관, 서울

사유의 깊이, 모란갤러리, 서울

1996 일산호수 조각공원 야외조각 심포지움, 고양시

‘96서울미술대전, 서울시립미술관, 서울

1995 오늘의 조각전, 종로갤러리, 서울

환류(還流)-한일현대미술전, 나고야시립미술관, 나고야, 일본

1994 한국현대미술의 동향전, 인사갤러리, 서울

1993 작은 조각 트리엔날레 ‘93, 워커힐미술관, 서울

12월전, 그 10년후, 덕원미술관, 서울

1992 생명을 찾는 사람들, 국제화랑, 서울

토탈미술대상전, 토탈미수관, 장흥

1990 ‘90 현대미술초대전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

‘90 새로운 정신전, 금호미술관, 서울

1945-1990판문점과 브란덴부르크, 시공화랑, 서울

예술의전당 개관기념전, 서울

1989 갤러리서미 개관초대전, 갤러리 서미, 서울

작은 조각전, 갤러리 서미, 서울

1988 한국현대미술전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

1987 동서의 융합, East-West Center, Hawail, 미국

갤러리현대 개관기념 ‘80년대 작가전, 갤러리 현대, 서울

1986 오늘의 현대조각가 10인전, 바탕골미술관, 서울

참고문헌

2016 심상용, 미적 송과선(松果腺, pineal gland), 그리고 0.5cm 남짓의

함몰부에 고여있는 조각론, 인당뮤지엄

김정락, 오롯이 존재하는 조각, 인당뮤지엄

2013 심상용, 확대된 사유에 의해 절제되는 개방, 관계, 연대의 예술론, 갤러리 시몬

2012 심상용, 드로잉의 두 호흡, 갤러리 두인

2010 김정락, 시간의 과정을 기억하는 조각, 월간미술 12월호

2007 최태만, 한국현대조각사연구, 아트북스, 모란미술관

2006 정신영, 들고나고, 현대미술로의 초대, 서울대학교 미술관

2004 최태만, 최인수展, 금산갤러리 전시립, 월간미술 11월호

2000 고충환, 명상으로 열린 원의 상징, 공간

1999 조광호, 무위의 이르는 길, 들숨날숨

1998 김정희, 물질과 작가의 흔적, 모란갤러리

1997 김용대, 사유의 깊이, 모란갤러리

1995 정헌이, 겸손함 뒤에 숨은 날카로운 의식, 가나아트

Kazuo Yamawaki, Circulating Currents-Japanes and

Korean Contemporary Art, Nagoya City Art Museum

1993 이종숭, 깊이 꿈꾸는 물질, 지각의 가능성, 그리고 숨쉬는 조각, 공간

정영목, 공간에 관한 개념적 명상, 토탈미술관

1992 이우환, 토탈미술관대상 심사, 토탈미술관

1985 이일, 인간과 더불어 있는 조각 ,공간

정병관, 구조와 표면의 길항작용, 한국미술관

수상

2001 제15회 김세중 조각상, 김세중기념사업회

1992 제2회 토탈미술상 대상, 토탈미술관

작품소장

국립현대미술관(과천), 서울시립미술관, 토탈미술관, 포항문화예술회관 대전정부청사,

용산구청, 한국통신, 올림픽조각공원, 용상조각공원, 일산호수조각공원, 연천한탄강 조각공원,

ASEM 빌딩, 상업은행 본점, 한미은행 본점, 국민생명본사사옥, 서울대학교 치과대학병원,

서울대학교 농업생명과학대학, 부천현대백화점, 서남권농산물센터, 청품호반,

사할린 코르샤코프 러시아

CHOI, In Su

Professor Emeritus, Seoul National University

M.F.A. in Fine Arts, College of Fine Arts, Seoul National University

Studied at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe

Solo Exhibitions

2016 Indang Museum, Daegu

Artlink, Seoul

2013 Gallery Simon, Seoul

Gallery Date, Busan

2010 Artlink, Seoul

2009 BIBI Space, Daejeon

2004 Keumsan Gallery, Seoul

1995 Gallery Seomi, Seoul

1993 Total Museum, Seoul

1991 Gallery Seomi, Seoul

1985 Hankook Gallery, Seoul

1982 Space Gallery, Seoul

Group Exhibitions

2015 The Sound of Things, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

2014 A Form as Thinking, Rediscovery of Drawing, Museum SAN, Wonju

White and White - Dialog Between Korea and Italy, Museo Carlo Bilotti, Rome, Italy

Trace of Korean Contemporary Art, Museum of Art Seoul National University, Seoul

Inauguration Exhibition, MMCA, Seoul

2012 Ceramics Commune, Art Sonje Museum, Seoul

Steel Life, Pohang Museum of Steel Art, Pohang

Drawings of two artists, Gallery Dooin, Seoul

2011 Qi is Full, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu

Sculpture’s Drawing, SOMA Museum, Seoul

2010 The Seoul Art Exhibition - Contemporary Korean Sculpture 2010, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2009 Yeoncheon International Sculpture Symposium, Yeonchen

2008 Scultura Internazionale ad Aglie, Scultura Natura, Torino, Italy

2007 Lines in Space, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan

Spirit of Contemporary Korean Spirit, Manas Art Center, Yangpyeong

2006 Simply Beautiful, Centre PasquArt, Biel, Swiss

Fluid Artcanal 06/07 International, Le Landeron, Swiss

Invitation to Contemporary, Museum of Art Seoul National University, Seoul

Silent Forest, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2005 Seoul Sculpture Society Exhibition, Insa Gallery, Seoul

2004 Spirit, Art and Calligraphy, Kim Jong Young Museum, Seoul

Stillness and Movement, SOMA Museum, Seoul

Looking Back to the Current of Contemporary Korea sculpture, Moran Museum, Namyangju

2002 Seoul Art Grand exhibition, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Inter - images "Void", Total Museum, Seoul

2001 Yongsan Family Park Sculpture Garden, International Sculpture Symposium, Seoul

2000 Mix-up, Total Museum, Seoul

Beyond the Circle, Moran Museum, Namyangju

1999 Space and Object, Busan Metropolitan Museum, Busan

Contemporary Korean Sculpture-1999, Gallery Wooduk, Seoul

1998 Material and the Touch of the Artist, Moran Gallery, Seoul

Olympic Park, International Sculpture Symposium, Seoul

1997 Nature and Thinking, Park Ryu Sook Gallery, Seoul

The Voices of Zero at Seong Gok Art Museum, Seoul

The Depth of Thinking, Moran Gallery, Seoul

1996 II San Lake Park, International Sculpture Symposium, Goyang

Contemporary Art in Seoul '96, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

1995 Sculpture Today, Jongno Gallery, Seoul

Circulating Currents-Korean and Japanese contemporary Art, Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya, Japan

1994 Tendency in Contemporary Korean Arts, Insa Gallery, Seoul

1993 Small Sculpture Triennial, Walker Hill Art Center, Seoul

December Show - After 10 Years, Dukwon Gallery, Seoul

1992 Artists - Searching for Life, Kukje Gallery, Seoul

Total Art Grand Prize Exhibition, Total Museum, Jangheung

1990 ‘90 Contemporary Art Exhibition, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Gwacheon

New Spirit, Kumho Museum, Seoul

1945-1990 Panmunjom & Brandenburg, Sigong Gallery, Seoul

Seoul Arts Center Inauguration Exhibition, Seoul

1989 Artist Today, Gallery Seomi, Seoul

Small Sculpture Exhibition, Gallery Seomi, Seoul

1988 Contemporary Korean Art Exhibition, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

1987 Harmony in East and West, East-West Center, Hawaii, U.S.A

Artists in 80s, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

1986 10 Contemporary Sculptors Show, Batangol Art Center, Seoul

Bibliography

2016 Sang-Young Sim, Aesthetic Pineal Gland: Sculpture Theory Pooled in a 0.5cm Concavity, Indang Museum

Jung Rak Kim, The Sculpture Existing as Itself, Indang Museum

2013 Sang-Young Sim, Solidarity Moderated by Enlarged Thinking, Gallery Simon

2012 Sang-Young Sim, Drawing of two artist, Gallery Dooin

2010 Jung Rak Kim, Vestiges of Time, Artlink, Review, Wolgan Misul, Dec.

2007 lae-man Choi, History of Contemporary Korean Sculpture, Artbooks, Moran Museum

2006 Shin-young Chung, To and fro, Invitation to Contemporary, Museum of Art Seoul National University, Seoul

2004 Tae-man Choi, Insu Choi Sculpture Exhibition, Kumsan Art Gallery, Review, Wolgan Misul, Nov.

2000 Chung-whan Ko, Symbolic Circle of Contemplation, SPACE

1999 Kwang-ho Cho, Path Towards Moo Wi, Deulsum Nalsum

1998 Jeong-hee Kim, Material and the Touch of the Artist, Moran Gallery

1997 Yong-dae Kim, The Depth of Contemplation, Moran Gallery

1995 Hoen-yi Choeng, Receptive eyes, Gana Art

Kazuo Yamawaki, Circulating Currents-Japanes and Korean Contemporary Art, Nagoya City Art Museum

1993 Jong-soong Lee, Dreaming Material, Possibility of another perception and breathing Sculpture, SPACE

Young-mok Chung, On meditative space, Total Museum

1992 Ufan Lee, Total Art Grand Prix, Total Museum

1985 II Yi, Sculptures with human being, SPACE

Byoung-guwan Chung, Antagonism between mass and surface, Hankuk gallery

Prize

2001 Total Art Grand Prize, Total Museum, Seoul

1992 Awarded Kim Sejung Sculpture Grand Prize, Seoul

Collections

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art(Gwacheon),

Seoul Museum of Art, Total Museum, Pohag Art & Culture Center,

Government Building Daejeon, Yongsan-gu Office, Korea Telecom,

Seoul Olympic Sculpture Park, Yongsan Sculpture Park, llsan Lake

Sculpture Park, Yeoncheon Hantan River, ASEM Building, Com

mercial Bank HQ, KorAm Bank HQ, Kookmin Life insurance Center

Building, Seoul National University Dental Hospital, College of

Agriculture and Life Sciences, Seoul National University, Hyundai

Department Store(Bucheon), West-South Agricultural Product Cente,

Cheongpung Lakeshore, Korsakov Sakhalin Russia

오롯이 존재하는 조각

김정락

미술사학 박사,

한국방송통신대학교 교수

창작행위의 궁극적인 힘은 어떤 것이고 또 어디에서 오는 것일까? 최인수는 그곳에 도달하는 것이 지난至難한 일임을 알면서도 조각가로서의 긴 여정을 거쳐왔다.자기성찰과 질문을 이어가며 존재하지도 않는 길을 만들며 헤쳐왔다. 그는 이렇게 진언하고 있다. “전의식前意識, 전논리前論理, 전이지前理知의 상태에서 삶은 춤추고 생생해진다.” 최인수는 수많은 사물과 현상을 두고 원천의 감성에 관해 소중히 그리고 부단히 사유해온 것으로 보인다. 이성적 시선이 사물을 관찰하고 계측할 때 감성적 시각은 이미 그것의 본질을 껴안고 개인을 넘어선다.

그는 조각에 의미나 메시지를 부여하기보다 “작업과정에 맡기고 그냥 충실히 따라간다.”라고 우회적인 대답을 던진다. 물질로부터 오는 저항이나 돌출하는 여러 난제들과 미묘함을 온몸으로 받아들이며 일한다는 뜻이 된다. 따라서 일은 어떤 형태를 만드는 수단을 넘어 작업 자체의 즐거움과 함께 정서적 생존에 대해 사유하게 한다. 이러한 태도는 서구의 예술론에 뿌리 깊이 박혀있는 변증법적 논리와 상반되는 것처럼 보인다.

예술 행위와 그 흔적이 오롯이 배어있는 최인수의 조각은 탈 기하학적이고 단순하며 질박한 형상을 띄고 있다. 그리고 그 촉각적 특성haptic sense은 은유적으로 청각적 상상력에 닿아있다. 눈요깃거리나 스펙터클과는 거리를 두는 그의 작품은 규모나 외형에서 대체로 절제된 모습을 띄고 있다. 무딘 시선은 그의 작품이 고졸古拙하거나 소탈하다고 평하기도 한다. 그의 작품에서 오는 단순성은 복잡하고 구체적인 외형을 압축하거나 개략적으로 정리한 것이기 보다 원래 그런 것처럼 보인다. 즉 분석적이고 기계론적 환원으로 추상의 단순성에 이른 것이 아니고, 그 자신의 고유한 근거와 논리에 의한 것이라는 점이다. 그의 작품에서 보여주는 형상 사고는 선험적a priori이고 감각성에 기인하는 것이라 하겠다. 그리고 그 감각성은 독특하면서도 매우 세련된 형태로 정제되어 있기에 언어로 그 형상성을 떠받치지 않아도 될 만큼 자립적이다. 그의 작품은 공간과 시간에 대한 독자적인 제안으로 시적 관조와 메타포를 허용한다. 열린 체계로서의 그의 작품이 모더니즘의 환원주의와 탈-리터러시post-literacy와 구별되는 지점이다.

대지(흙)는 인간존재에게 믿을 만하고 포괄적인 배경이 되고 근원적이고 원천적으로 좋은 것이기에 무엇인가 기준이 되어왔다. 흙은 여러 종교와 신화에서 생명의 근원으로 그리고 유한한 존재와 무한의 시간성에 관계되어 다루어져 왔다. 문화와 예술 전반에 걸쳐 흙은 소재로 다루어지고, 조각에서는 일반적으로 소조의 재료로 형태를 만드는데 사용된다. 조각가인 최인수는 흙이 지닌 특성을 작업의 의미와 연관시키며 이를 그 본령本領으로 삼는다. 흙은 가변성, 저항성, 흡수성과 유연성을 지닌 재료이다. 그는 지속적으로 흙에 귀 기울이고 대화하면서 흙의 시간이 자연스럽게 조각의 몸을 이루게 되기까지 반복하여 만들어왔다. 흙으로 만들고 청동으로 주조된 다면적이고 다각적인 굴곡을 지닌 <손으로 느끼는 삶>, <시간이 태어나다> 연작의 표면에는 손가락으로 눌러 새긴 음각의 형상들이 전체 형태에 다시점多視點으로 시각을 분산decentering vision시키며 각기 다른 시간적 템포와 리듬을 엮어 놓고 있다. 촉지觸知로 이어지는 그의 음각형상들은 고대 상형문자나 울주 천전리 암각화 그리고 한국추상미술에서의 이응로, 남관의 문자추상을 떠올리게 한다. 최인수의 경우 문자형상은 작품을 이루는 필수불가결한 기호이면서도 조각형태 전체를 사유하는 작가의 논리 방편이 된다. 그는 뛰어난 언해능력과 함께 이를 예술적 상상력의 자원으로 사용하고 있다.

전시장 바닥에 태연히 놓여있는 길거나 짧은 <먼 곳으로부터 오는 소리>와 <길> 연작은 작업실 바닥에서 흙덩어리를 굴리고 석고로 떠서 철로 주물한 것이다. 표면에는 굴려졌던 장소와 시간, 주철의 과정 그리고 천천히 녹슬어가는 아날로그적 시간이 기록되고 동시에 엔트로피의 증가에 따른 파토스pathos가 묻어난다. 수메르Sumer의 돌도장에 새겨진 그림이나 글씨가 진흙판 위에 굴려져 부동의 시간이 재현된 것에 비하면 그 표면이 숨 쉬는 듯한 최인수의 작품은 그자체가 시간을 머금고 있다.

조각 작품으로서의 대상과 그것을 가능케 한바닥이나 두 손안의 공간은 서로가 유무상생有無相生으로서 존재이유가 된다. 이렇게 하여 생명감은 처음부터 배태胚胎되고 충일해지는 것이다. 작업실 바닥에서 앞으로 뒤로 굴려지면서 만들어진 작품은 그 자체가 길을 은유한다고 볼 수 있다. 이는 머무는 장소가 아니라 유동적으로 엮어지는 행위와 그 시간을 담고 있는 중층의 공간이 되기 때문이다. <들고나고> 연작에서는 한 덩어리의 흙이 재사용되어 동일한 질량을 지닌 형태들의 변주를 이루며 바닥위에서 공간의 짜임을 보여주고 있다. 촉각적인 감각은 그의 흙 작업에서 또다른 모습으로 전개된다. 그냥 두 손 안에서 둥글리어 빚은 작은 흙덩어리, 건조 후 고온에서 구워낸 <태고의 바람> 연작은 내밀하면서 무한한 느낌으로 각별한 심미적 분위기를 자아낸다. 오직 손만으로 만든 즉 인류 최초의 작업행위가 예술 작품의 원리적인 기능으로 돋보인다. 누구라도 작가의 손이 지녔던 온기와 호흡을 느끼게 되고 가장 기본적이고 시원적인 조형언어가 인간의 위대한 시가 되는 것이다.

최인수는 흙 작업을 주로 따뜻한 계절에 하고 추운 계절에는 다른 재료로 작업한다고 한다. 산업에서 생산의 효율성을 제고하는 선형적이고 직선적인 시간 사용에 비하여 그의 시간이해는 자연의 흐름과 몸의 형편을 따르는 다시간적多時間的이고 비선형적이다. 그의 작업이 억지스럽지 않고 자연스럽게 드러나 보이며 관조로 이어지는 소이所以라 하겠다. 스테인리스 봉을 짧게 자르고 다시 이어가며 용접하여 만든 <나오다가 숨다가> 연작에서 덩어리나 물질적 존재감은 극소화된다. 체적은 선적線的 구조의 표면으로 전환되고 벽면 공간과의 접면을 따라 시선은 이동하고 긴장감과 함께 공기적 상상력이 배가 된다. 흙 작업이나 금속작업에서 그가 재료를 다루는 방식은 하나같이 기본적이고 가까운 것들인데도 느낌은 항상 새롭다. 그는 어린 아이처럼 굴리거나 자르고 다시 연결하는 행위를 통해 독자적인 리듬과 공간 지각을 가능케 하고, 놀이하듯이 어떤 경계에 매이지 않고 자발적이고 유연하게 일한다. 그래서 쓸모가 고려되지 않는 “처음의 시간”에 가 닿고 있는 것이다.

최인수는 조각의 정체성을 괴체에서 표면으로 연장하면서 기존의 조각들이 가졌던 동질성의 공간을 넘어선다. 그래서 사소하고 비본질적으로 보이던 것들은 측량하기 어려운 깊이와 무게를 지닌 것으로 전환되고 존재하지 않았던 전혀 다른 실재에 이르고 있다. 그는 “조각이 말하게 한다. 그리고 듣는다”라고 말한다. 그의 사유는 깊지만 우리를 짓누르거나 그 미로 속으로 구속하지 않는다. 그의 작업은 철학이나 명분을 추종하는 공허함이 아니고 오히려 그런 것들을 해체하고 의미 쌓기를 버림으로써 진정한 의미에 닿고자하는 것으로 보인다. 마치 ‘부처를 만나면 부처를 죽여라’라는 선승 임제臨濟의 경구처럼.

미적 송과선松果腺, pineal gland, 그리고

0.5cm 남짓의 함몰부에 고여있는 조각론

심상용

미술사학 박사,

동덕여자대학교 교수

시간의 얼굴, 과도함과 공허의 인장력이 밀고 당기는 곳

최인수의 세계는 시종 질료주의, 곧 관념주의와 상반된 것으로서 질료주의와 무관하다. 흙을 인식하고 경험하는 그의 태도와 태도에 깃든 관점은 내게 그렇게 읽을 근거로서 부족하지 않다. 이 세계에서 흙은 단 한 번도 주체와 분리된 객체, 중성적인 재료나 건조한 물성物性, 또는 표현을 이끄는 도구로 규정된 적이 없다. 흙은 늘 대지의 연장, 식지 않은 체온, 포획되지 않은 포에지poesie거나 그 이상이다. 이를테면 정복되기를 거부하는 대지大地, 취급될 수 없는 생생함, 그리고 정당화되기를 거부하는 형태이다. 하지만 이조차도 조야粗野한 접근일 뿐임이, 최인수의 <시간의 얼굴,Faces of Time>연작(2016) 앞에서 자명해진다.

너무 많은 미학이, 그리고 너무 살찐 것들의 미학이 휩쓸고 지나간 탓에 이 시대는 오직 상실의 미학 하나만을 부둥켜안고 있는 것 같다. 동시대의 미술은 피폐한 풍요에서 풍요로운 피폐 사이를 메트로놈처럼 규칙적으로 오간다. 뒤샹Marcel Duchamp과 라우센버그Robert Rauschenberg와 아르망Fernandes Armand이 ‘reality’의 단초랍시고 하나둘씩 주워모으기 시작하더니만, 어느덧 거대한 폐자재 재활용 공장 같은 예술의 시대가 도래했다. 워홀은 TV에서 영감을 얻다가 아예 TV스타가 되는 길로 접어들었고, 데미언 허스트Damien Hirst의 세대는 다이아몬드에 눈먼 시대를 일깨우는 대신 그 변호사가 되기로 작심했다. 인상주의 이래로 예술 세계는 과도하게 밝아졌고, 대전 이후론 고도비만을 앓고 있다. 하지만 의미의 휘도는 오히려 더 결핍되고, 나아갈 미학의 길은 거의 막히다시피 했다. 천정을 뚫고 들어와 어두운 실내를 밝히는, 예컨대 카라바조Caravaggio와 렘브란트Rembrandt H. van Rijn의 한 줄기 빛의 갈증이 여전히 목을 타게 만든다.

이 시대에 홍수를 이루는 망막주의에 먼저 경종을 울려야만 할 것이다. 과도한 스펙터클리즘, 마케팅과 돈벌이의 미학, 국가홍보대사 예술론의 반대쪽엔 또 다른 늪지가 조용히 입을 벌리고 있다. 존 케이지나 머스 커닝햄Merce Cunningham로 대변되는 이 세계는 모든 물질과 행위뿐 아니라 심지어 의지까지 거부해야 할 목록에 포함시킨다. 철저한 비非계획과 우연이 추구되고, 허공에 나뭇조각이나 동전을 던지는 점성술이 신뢰되고, 이성의 범접을 불허하는 ‘저 너머 어디’가 궁극으로서 규정되는 그런 세계다. ‘비평이 곧 예술’이라는 코수드Joseph Kosuth나 회화의 물리적 지지대를 박탈한 로렌스 와이너Lawrens Weiner의 ‘신체 없는 회화’, 요셉 보이스의 ‘개념 조각’ 등이 이 거창해 보이지만 밋밋하기 짝이 없는 계열의 산물들이다. “프랑스에서 지식인인 척하려면 비관주의자가 되어야 할 필요가 있다”라는 베르트랑 라비에Bertrand Lavier를 떠올려야 하지 않을까? 이 비아냥이 사실무근인 것은 아니다. 이 일련의 케이지주의자들은 과도하게 엘리트적이어서 최소한의 감흥도 주지 않기 위해 최선을 다하는 것 같다. 이들은 무시하고, 없애고, 외면하고, 증발시키면서 부정과 부재의 예찬으로 나아간다.

최인수의 <시간의 얼굴>을 마주하는 곳이 바로 이곳, 과도함과 공허가, 과도한 조명과 어두움의 인장력이 드세게 교차하는 세상임을 잊지 말자. 그러니 주의를 기울여야 마땅하다. 최인수가 질료와 망막과 표현을 내려놓았다고 해서 곧장 일련의 케이지주의로의 편승으로 읽어선 곤란하다. <시간의 얼굴>이나 <나오다가 숨다가>가 “파도처럼 변화무쌍한 인생”-몽테뉴가 그렇게 말했다-을 펼치는 대신 오히려 접어나간 건 사실이지만, 그것이 세상과의 단절이나 관념의 유희로의 선회를 의미하는 것도 아니다. 이 세계는 지성의 오만한 끝을 구부러뜨리고, 감정의 숱한 요철을 쳐낸 결과 작고 느슨하게 둥근 것이 되었지만, 세계의 얼굴은 삭감되지 않은 채 남아있다.

미적 송과선(松果腺, pineal gland)

최인수의 미학은 물성이 지나치게 비대해져 반사적으로 유물론을 웅변하는 조각, 이를테면 마초성, 팽창한 부피, 스테로이드 근육질로 묘사되는 또는 남아도는 시간을 위한 오락거리나 호사스러운 취향으로 정당화되는 것의 대척점에 위치해 있다. <시간의 얼굴>은 이 미학의 탈권위적, 탈 가부장적 지평을 잘 보여준다.

<시간의 얼굴>은 이미 마초적 기념비성과 첨단 기술에 대한 명백한 거부의 산물이다. 그리고 모든 완화된 각을 끼고 이어지는 부드러운 면들, 그리고 그 한 지점에 존재하는 오목하게 패인 작은 함몰이 특별히 중요하다. 그것은 불에 구워지기 전 무언가에 의해 남겨진 자취다. 사건의 흔적, 또는 그저 세계의 각인일 수도 있다. 사건은 종료되었지만 흙은 그것을 잊지 않고 있다. 그 크기는 0.5~1cm를 벗어나지 않는다. 거의 송과선pineal gland의 크기와 유사하다. 송과선은 성인의 경우 0.5cm 남짓의 크기에 무게는 0.1g을 조금 넘는다. 그 생김새가 솔방울과 닮은 것에서 명칭이 유래한 작은 기관은 뇌의 한 부분인 간뇌의 천장부에 위치해 있으며, 진화론적으로 눈의 전구체였던 것으로 알려져 있다.

프랑스의 철학자이자 생리학자였던 르네 데카르트René Descartes는 이 엷은 선홍색이나 회색의 작은 기관에 이례적으로 주목했다. 여타 척추동물들과는 달리 사람에게 있어서만은 송과선의 기능과 역할이 불분명했기에, 데카르트는 이 기관이 정신과 육체의 상호작용을 주선하는 역할을 담당할 거라고 생각했다. “정신과 육체를 뒤섞어 하나의 전체”로 반죽하는, 육체적 경험이 영혼에 전달되고 영혼이 즉각 신체 작용으로 이전되는 물성物性과 심성心性의 교환이 일어나는 장소로 여겼던 것이다. 데카르트는 “영혼이 작용하는 신체 부위는 심장이나 뇌수 전체가 아니라 단지 뇌수의 모든 부분 가운데 가장 내밀한, 아주 작은 부분 어떤 선腺임이 분명하다”라는 자신의 가설을 의심하지 않았다.

신체의 특정 부위에 영혼이 깃든다는 것은 물론 가설에 지나지 않는다. 그렇더라도 <시간의 얼굴>과 그 표면에 패인 0.5cm 남짓의 함몰부에 대한 메타포로선 더없이 유효하다. 전술했듯 이 세계는 물질 자체뿐 아니라 엘리트 관념주의에도 전혀 현혹되지 않는다. 그는 유물론자가 아니기에, 예컨대 바타이유Georges Bataille가 그렇게 했던 것처럼 물질로부터 대안을 구하는 쪽으로 나아갈 수는 없다. 같은 맥락에서 고상한 사변으로부터 구원을 모색할 수도 없다. 사실 사유야말로 시각보다 훨씬 더 가변적이지 않던가. 흄David Hume이 말했듯, “눈이 눈구멍 안에서 회전하면 지각은 반드시 바뀐다.” 최인수에게 물질은 사변 이상으로 중요하다. 그는 조각가다! 조각가는 이 사실을 운명적으로 믿고 받아들인 사람이다.

하지만 여기에 단서가 없을 수 없다. 물질은 최소의 의미에서만, 즉 자유분방한 사유를 진실의 기둥에 묶는 동기 안에서만 조심스럽게 신뢰되어야 한다. 그렇게 하는 방식을 내놓는 것이 특히 조각가에게 주어진 소임이라는 사실을 그가 모를 리가 없다. 조각가는 그것에 심취하기 위해서가 아니라 그 심취에서 깨어나기 위해, 즉 매몰되기 위해서가 아니라 매몰로부터 기어 나오기 위해 물질의 전문가가 되어야만 한다. 그리고 정당화된 믿음인 지식에 의해서가 아니라 아직 정당화되지 않은 지식인 감각의 통제 아래 그것-물질-을 올바로 정치正置 시킬 수 있어야 한다. 최인수의 조각 미학의 말하는 바가 이것이다. 물질에 매몰되지 않는 것만큼이나 철학적 명제의 수준으로 후퇴하거나 신비의 어두운 방을 붕붕 날아다니지 않는 것이 중요하다! 미적 혁신은 언제나 이 양자 사이의 투쟁에서 비롯되었다. 이 두 극단이 첨예하게 교차하는 지점들 가운데 한 정교한 지점에서, <시간의 얼굴>과 0.5cm 남짓의 함몰부에서 최인수의 미학이, 조각론이 그리고 모습을 드러낸다. 데카르트가 주목했던 정신과 물질의 길항(拮抗)적 교차 지대로서 송과선의 미적 차원으로서 말이다.

보이지 않는 세계를, 하지만 보이지 않는 세계로서의 위상을 간직한 채 보이도록 하는 것이 어떻게 가능할까. 이 과제야말로 칸딘스키에서 폴록에 이르는 수많은 추상작가들이 위험을 무릅쓰고 무의식의 심연과 신비의 경계를 넘나들어야만 했던 이유가 아니겠는가. 최인수의 세계가 얼핏 사변적인 것으로 보이는 것은 그가 그 경계를 이제까지의 통상 그렇게 했던 것보다 더 멀리까지 밀어붙이는 데 성공했기 때문일 것이다.

최인수는 0.5cm 남짓의 함몰부에 의심하고, 이해하고, 구상하고, 긍정하거나 부정하고, 바라거나 거부하는 모든 정신의 덕을 포에지의 형태로 함축해 놓았다. 즉 그것을 아주 조금 보이도록 했다. 거기까지가 물성의 최대 허용치다. 그 이상은 보여줄 수 없다. 더 보여주기 위해서는 조직해야 하고, 조직하는 과정에서 물질적 기만이 개입되는 것을 막을 수 없기 때문이다. 0.5cm 남짓의 함몰부는 최인수의 미학을 대변하는 미적 송과선이다. 그곳은 가장 정교하게 계량된 물성과 가장 시적으로 조율된 사유가 교차하는 장소다. 이 작고, 완곡하고, 공굴려진 평화로운 세계의 긴밀한 꼭짓점이다.

The Sculpture Existing as Itself

Kim, Jung rak

Art Historian, Professor,

Korea National Open University

What is the ultimate power of creation and where does it come from? Insu Choi has travelled a long way, knowing that it would be a difficult task to reach his destination. While continuing self-introspection and inquiry, he has paved roads that previously did not exist. He states as follows: “Life dances and becomes more vivid in the state of pre-consciousness, pre-logic and pre-intellect.” Choi appears to have preciously endlessly contemplated on source of sensibility concerning numerous objects and phenomena. While the rational gaze observes and measures objects, the emotional vision already embraces their essence and transcends the individual.

Rather than giving significance or messages to his sculptures, he explains in a roundabout way that he “leaves it to the work process, and just follows it faithfully.” That is to say he works as he accepts all the resistance from the material, the various difficult problems that protrude, and subtleness with his whole body. Therefore, the work goes beyond being a means to make a certain shape, providing pleasure of work itself and enabling us to contemplate on emotional survival. Such attitude seems to contradict the dialectic logic deeply rooted in Western art theory.

Choi’s sculptures, in which the acts of art and traces are permeated, take a post-geometrical, simple and plain form. And the haptic sense metaphorically touches upon the auditory imagination. His works, which distance themselves from feats for the eye or spectacles, generally show moderate appearances in terms of scale or exterior form. Beholders of dull eyes sometimes evaluate his works as artless or unceremonious. The simplicity of his works is not a result of compressing or roughly organizing complex and concrete forms, but appears to have been that way originally. In other words, he did not reach abstract simplicity through analytical and mechanical reduction, but through his unique grounds and logic. The formative thought shown in his works are a priori, and originate from sensibility. Moreover, as such sensibility is not only peculiar but is also refined as a very elegant shape, it is independent to the extent that it does not require support for its formativeness through language. His works are independent proposals concerning time and space, and allow poetic contemplation and metaphor. This is the point where his works, as open systems, may be distinguished from modernist reductionism and post-literacy.

The earth (soil) has been a trustworthy and comprehensive background to human beings. As it is something fundamentally good, it has served as a certain standard. In diverse religions and mythology, earth has been considered the origin of life, and has been dealt in relation to finite beings and infinite time. Earth is used as subject matter throughout culture and art, and in sculpture it is generally used as a material for modeling. Sculptor Insu Choi links the characteristics of earth to the significance of his work, and sees it as the proper function of sculpture. Earth is a material with variability, resistance, absorbance and flexibility. The artist continuously listens to the earth and converses with it repeatedly until the earth’s time naturally becomes the body of the sculpture. On the surfaces of the series, Touch, and Faces of Time, which were made with earth and casted in bronze, and have multilateral and diverse bends and curves on them, there are engraved shapes made by pressing the material with the artist’s fingers. These forms decenter the vision of viewers through multi-perspectives throughout the overall surface, thus interweaving different temporal tempos and rhythms. His engraved forms, which lead to tactile perception, remind us of ancient hieroglyphs, the Cheonjeonri rock engraving in Ulju, and the letter abstractions by Lee Ungno and Nam Kwan in Korean abstract art. In the case of Choi, the letter figures are not only essential signs that form the work, but also the logical means of the artist to contemplate on the whole shape of the sculpture. Based on his outstanding annotation skills, the artist uses them as resources for his artistic imagination.

The long or short works casually placed on the floor of the exhibition room, titled At The Edge of Sound, or Path were made by rolling lumps of clay on the artist’s studio floor, making plaster casts, and then casting them in iron. The place and time it was rolled, the process of iron casting, and the analog time of the slow rusting process are documented on its surface, and at the same time, the pathos according to the increase of entropy is smeared onto it. Compared to the pictures or text engraved on the Sumer stone seals, which were rolled on clay surfaces to represent static time, Choi’s works seem to have breathing surfaces, and to be holding time within them.

The subject as a sculpture work, the floor that made it possible, and the space within the artist’s two hands are mutually relative and each become one another’s reason for existing. Hence, the sense of life was conceived and made exuberant from the beginning. The work made by rolling it forward and backward on the studio floor can be seen as a metaphor of the road in itself. This is because it becomes not a place where one dwells but a multi-layered space containing the fluidly interwoven behavior and its time. In the series In and Out, a single lump of clay is reused to form a variation of shapes with identical mass, presenting a composition of space on the floor. Tactile sense unfolds in a different appearance in his earth work. Prehistoric Winds series, which were made by just rolling small lumps of clay between his two hands, drying them, and firing them at a high temperature, evoke a special aesthetic atmosphere with an intimate and immense feeling. The fundamental function of the art work—recalling the first artistic act by humankind—stands out. Anyone can feel the warmth and breath of the artist’s hands, and the most basic and primeval formative language becomes a great poem of humanity.

It is said that Insu Choi mainly works with clay during the warm seasons, and uses different material in the cold season. Compared to the linear and forthright use of time in industries, which take priority in enhancing productivity, Choi’s understanding of time is multi-temporal and non-linear, as he follows the flow of nature and the condition of his body. That is why his work does not seem obstinate but reveals itself naturally, and leads us to contemplation. In the series, Appear and Disappear, which was made by cutting a stainless steel rod into short pieces and then welding them together, the sense of mass or material existence is minimized. The volume is transferred into the surface of linear structure, and as viewers’ eyes move along the area touching the wall, tension and imagination are doubled. The way he treats material in his clay work or metal work is always basic and familiar; however, the feeling is always new. Through the child-like acts of rolling, cutting, and reconnecting, he enables independent rhythm and spatial perception. Like a play, he works voluntarily and flexibly without being bound to any border. Thus he touches the “time of the beginning,” of which use is not considered.

By extending the identity of sculpture from mass to surface, Insu Choi has transcended the space of homogeneity held by existing sculptures. Hence, the things that appeared as trifling and unessential were transferred into things with unfathomable depth and weight, reaching a completely different reality. He says, “I let the sculpture speak. Then I listen.” His thought is deep, but it does not oppress us or constrain us with its labyrinth. He does not pursue the emptiness of philosophy or cause, but seems to be trying to reach true meaning by deconstructing such things and discarding accumulation of significance. It is like the aphorism by the priest Im Je, who said, “If you meet Buddha, kill him.”

Aesthetic Pineal Gland: Sculpture Theory

Pooled in a 0.5cm Concavity

Shim, Sang Yong

Ph.D. Art History, Professor,

Dongduk Women's University

Faces of Time: The Push and Pull of Tension Between Excessiveness and Emptiness

The world of Choi Insu has always been unrelated to materialism, i.e., materialism as opposed to idealism. His attitude of perceiving and experiencing earth, and the perspective indwelling in this attitude, are enough grounds for me to make such a presumption. In this world, earth has never been defined as an object separated from the subject, a neutral material with dry material property; or a tool for such expression. Earth has always been an extension of the land, body heat that has not cooled down, uncaptured poesie, or more. It is a land that refiises to be conquered, a vividness that cannot be handled, and a shape that refuses to be justified. But the fact that even these arc merely coarse approaches is made clear in artist Choi Insu’s series Faces of Time (2015).

Having suffered the storm of too much aesthetics and aesthetics of excessively fleshy things, this era now seems to be clinging only to the aesthetics of loss. Contemporary art rocks back and forth like a metronome, between impoverished abundance and abundant impoverishment. Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg and Fernandes Armand began picking up and gathering so-called clues of "reality,” and what soon arrived was an era of art resembling a gigantic, wasted-resources recycling plant. Warhol got his first inspirations from TV only to pursue becoming a TV star; Damien Hirst’s generation decided not to enlighten a time blinded by diamonds, but rather to become its lawyers. Since Impressionism, the world of art has become excessively bright, and since the World Wars it is suffering from extreme obesity. Nevertheless, the brightness of meaning is more deficient, and the future path of aesthetics is nearly closed. Thirsting for a single ray of light coming through the ceiling to brighten the dark room, for instance, the light of Caravaggio and Rembrandt H. van Rijn, we continue to feel parched.

An alarm must first be raised against the “retina-centrism” that is flooding this era. On the opposite side of excessive spectacleism, the aesthetics of marketing and money-making, and the theory of art based on national promotion ambassadors, another swamp quietly awaits us with its mouth open. This world, represented by John Cage and Merce Cunningham, includes not only all material and action, but also will, in the list of things that must be rejected. It is a world where thorough non-planning and coincidence are pursued, and “somewhere beyond,” which prohibits the approach of any reason, is defined as the ultimate. Joseph Kosuth, who said “criticism is art,” Lawrence Weiner’s “painting without body” which omitted the physical support of painting, and Joseph Beuys’s "'conceptual sculptures” were products of this categoiy - seemingly grandiose but utterly dull. Should we not recall the words of Bertrand Lavier, who said, “To pose as an intellectual in France, one must become a pessimist”? This sarcasm is not groundless. The above-mentioned Cageists are overly elitist, and seem to be doing their best not to give the least bit of inspiration. They advance towards praise of negation and absence as they ignore, eliminate, avoid and vaporize.

Let us not forget that Choi’s Faces of Time faces this world, with its tension between excessiveness and emptiness, excessive lighting and darkness, as they roughly intersect with each another. Hence, caution is required. Just because Choi has set aside material, retina and expression does not mean that we can read him as siding with the Cageists. While it is true that Faces of Time and Appear and Disappear do not unfold a “life ever-changing like waves” - as expressed by Montaigne - but on the contrary; fold it, this does not indicate a severance with the world or a turn toward conceptual play. As a result of bending the arrogant tip of intellectuality and removing the numerous bumps of emotion, the world has become a small, loosely rounded thing; however, the face of the world remains uncut.

Aesthetic Pineal Gland

Choi Insu’s aesthetics are positioned at the antipodal point fr이n sculptures that reflexively speak for materialism due to hypertrophy of materiality, such as those characterized by machismo, expanded volume or steroid muscle, or those that are justified as entertainment for leisure time or luxurious taste. Faces of Time well represents the post-authoritarian, post-patriarchal horizons of such aesthetics.

Faces of Time is already a product of the clear rejection of macho monumentality and cutting-edge technology. Furthermore, all the soft surfaces that meet at eased angles, and the small, indented concavity that exists at a certain point, are especially important. This is a trace left by something before it was baked in fire. Perhaps it is a trace of an event, or just an engraving of the world. The event has ended, but the clay has not forgotten about it. Its size never exceeds 0.5∼ lcm in diameter. It is similar to the size of the pineal gland. An average adult has a pineal gland that measures about 0.5cm in size and weighs a little more than 0. lg. This small organ, named for its resemblance to a pine cone, is positioned in the brain at the ceiling of the diencephalon, and in terms of evolutional theory is known as the precursor of the eyes.

French philosopher and physiologist Rene Descartes took exceptional interest in this little, light-scarlet or gray organ. As the function and role of the pineal gland was unclear in the case of humans, unlike other vertebrates, Descartes thought it must play the role of mediating the interaction between the mind and the body. He considered it a place of exchange between body and soul, where the physical experience is communicated to the soul and the soul is immediately transferred to physical action, thus “mixing mind and body into a single whole.” Descartes never doubted his hypothesis that “the body part where the soul acts upon is not the heart or entire brain, but a very intimate, small part amidst the parts of the brain.”

Of course, to say that the soul is joined with a certain part of the body is nothing but a hypothesis. But even so, it could not be more valid as a metaphor for Faces of Time and the small concavities formed on its surfaces. As I men-tioned before, Choi’s world is not dazzled by material per se, or by elitist idealism. As he is not a materialist, he cannot go in the direction of finding alternatives from material, as in the case of Georges Bataille. In the same context, neither can he search for deliverance in elegant speculation. Isn’t thought much more variable than vision? As David Hume said, “Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying their perceptions.” To Choi Insu, material is even more important than speculation. He is a sculptor! A sculptor is someone who has believed and accepted this fact as fate.

Still, there has to be a clue here. Material must be trusted cautiously only in its minimum sense, that is, within its motivation to bind free thought to the column of truth. There is no way he does not know that presenting methods for this is the duty given to the sculptor in particular. The sculptor must become a specialist in material, not absorbed in it but awakened from such absorbtion, i.e., not buried in it but crawling out from it. He must be able to properly orient it - material - not according to knowledge, which is justified faith, but under the control of the senses, which have not yet been justified. This is what Choi’s aesthetics of sculpture is telling us. Not to retreat to the state of philosophical propositions and not to buzz around the dark room of mystery are as important as not to be buried by material! Aesthetic innovation has always been caused by the struggle between these two. It is at a point where these two extremes sharply intersect that Choi Insu’s aesthetics and theory of sculpture reveal themselves —in Faces of Time and the concavity with a diameter of approximately 0.5cm. It is the aesthetic dimension of the pineal gland as an antagonistic crossroads of the soul and material, as in Descartes’ conception.

How is it possible to make an invisible world visible while preservdng its status as invisible? This task is indeed the reason why so many abstract artists, from Kandinsky to Pollack, risked traversing the boundaries of the abyss of unconsciousness and mystery. The reason Choi Insu’s world at first sight looks speculative is because he has successfully pushed such boundaries further than others.

Choi has implied all the virtues of the soul that doubt, understand, compose, confirm or deny, wish for or reject, in his concavity, measuring about 0.5cm in diameter, in the form of poesie. That is, he made it so it would show very little. That is the maximum limit of materiality that is allowed. Anything exceeding that cannot be shown. To show more, one must organize, and in the process of organizing one cannot stop the intervention of material deception.

The 0.5cm concavity is the aesthetic pineal gland representing Choi Insu’s aesthetics. It is where the most elaborately measured materiality and the most poetically tuned contemplation intersect. It is the intimate vertex of this small, gently rounded, peaceful world.